Sometimes I don’t know my name

Does having more than one name mean having more than one identity?

A friend from university had the theory of steak and salad names. Maria is rarely used by itself in Latin America, so she thought double names with Maria went well together. Maria was the side salad and the other name was the steak. However, she was outraged to hear two steak names together. Who would have two main dishes without sides?

At that time, I didn’t think this was an issue. People with more than one name tend to identify themselves with just one. Maybe the one our family used to call us when we were little, or the one our teachers used at school. The one that got attached to our identity without consent from a very young age, leaving the other name(s), whether they are steak or salad, downgraded from full word to an initial when filling out forms.

When living in Argentina, Maria was my salad name, Pia was the steak, and everyone knew me by Pia. If I was introducing myself in a new context, there was no need to explain that I was also Maria because everyone in my culture knows that if you are called Maria Something you go by your middle name, the steak name.

If someone said Maria on the street, I would most likely not take notice. If we got a call at home asking for Maria, I would ask “Which Maria?” since my sister is also Maria Something. I was just Pia, without question or hesitation, and Maria was the side name so that Pia, which has only three letters, would not look so short when written down. In the spoken language, Maria didn’t identify me.

When I started traveling, my identity became more complex and the answer to the simple question “What is your name?” began to depend on the context. Today, I sometimes call myself Maria, something I hadn’t done before in Argentina.

The first reason for this change in self-perception is language. In English, I have to explain how to spell Pia, especially when speaking on the phone. “With P as in Peter”, I have to add so that my interlocutor doesn’t call me Bia. In Arabic, it is even more complicated because the sound of /p/ does not even exist. Sometimes I catch my Yemeni family saying Bia instead of Pia. Even though they can pronounce the /p/, their lips betray them and their mother tongue forces them to change the foreign sound for the familiar one.

On the contrary, Maria leaves no room for doubt and has become my public name when I make a reservation at a restaurant, call a 0-800 number, or introduce myself at work or social gatherings with people I don't normally hang out with.

I know a lot of people who feel the same way. My friend Nahuel gave up trying to teach Australians how to pronounce his name and, in the land of kangaroos, he is now known as Nick. My colleague from Taiwan calls herself Alice, and none of us know exactly what her name in Taiwan is. One day she introduced herself as Cécile when speaking French and we were amused to learn she had adopted several names depending on the language.

My other reason for using Maria in the United States is to hold on to my Latina identity. Calling myself Maria and pronouncing it with my Argentine accent is also a way of saying that I am Latin American and speak Spanish. An effort to preserve my roots, which become stronger with time and the miles traveled.

It’s clear to me now that Maria has also become a steak name and sometimes, I feel like a spy with a double identity depending on where I am.

If you have more than one name, do you have more than one identity as well?

In the U.S., National Hispanic Heritage Month is celebrated from September 15 to October 15 and there are a lot of events all over the country. This week, I’m lucky to have tickets to go listen to Sandra Cisneros, a writer I deeply admire.

In her book The House on Mango Street, the protagonist reflects on her name as a Mexican girl living in the U.S. Esperanza says:

At school they say my name funny as if the syllables were made out of tin and hurt the roof of your mouth. But in Spanish my name is made out of a softer something, like silver, not quite as thick as sister's name Magdalena--which is uglier than mine. Magdalena who at least can come home and become Nenny. But I am always Esperanza.

I would like to baptize myself under a new name, a name more like the real me, the one nobody sees. Esperanza as Lisandra or Maritza or Zeze the X. Yes. Something like Zeze the X will do.

I don’t know what Esperanza’s life would be like as Zeze the X, but she made me think if I would like to be called something else. To be honest, I don’t think so. But if my name, a part of my identity I thought was inalterable, has evolved with time, I might adopt a new name when I’m older. Maybe Sandra Cisneros will have some suggestions when I see her this week.

Until then, I cannot make up my mind on how to sign this publication, so I’m going to use all the possible combinations.

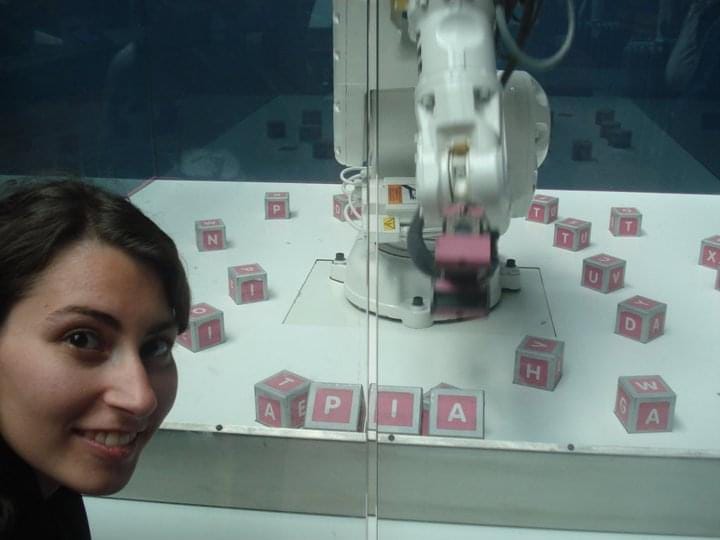

Greetings from Maria Pia / Maria / Pia / M. Pia

This is a great explanation of the importance of names and identity. As an Australian, i always get frustrated with my compatriots lazy way of anglicizing names, as your friend Nahuel experienced. Even on the phone to govt departments etc I ask for people's names and if I am unfamiliar with it, ask am i pronouncing it correctly. Names are so important. We do curate our identities in different cultures, to be sure.