“Every one of us has a linguistic history, however buried or unexamined. This, very briefly, is mine.” —Ross Perlin, Language City

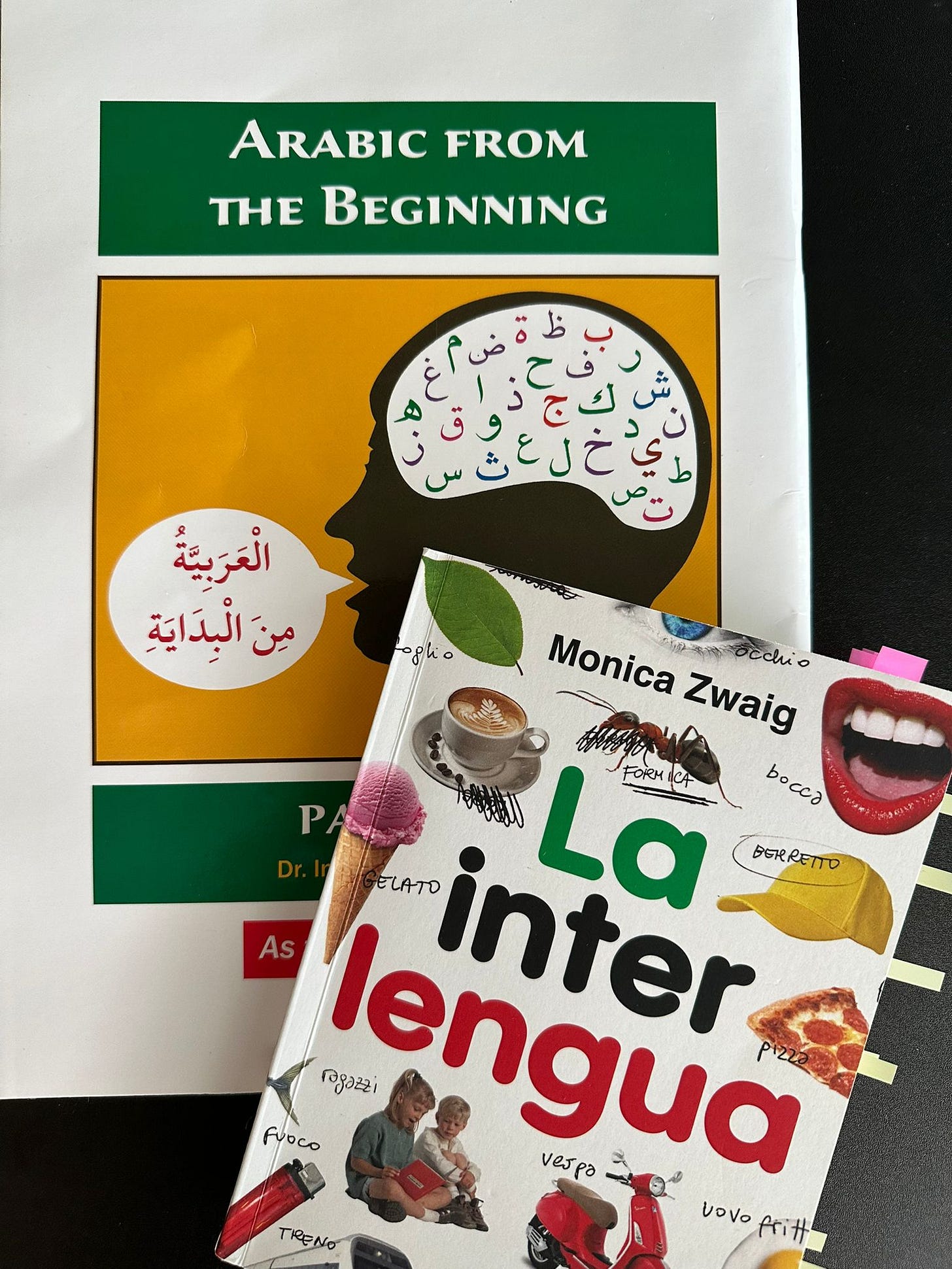

If you opened my brain today, I’m sure it would be a colorful map. Two main colors would show where the Spanish and English metropolises are. A vibrant glow would reveal the Portuguese neighborhood. A bright color would tell you where Arabic lives, a spacious home under constant renovation, with new rooms slowly but steadily taking shape. And scattered across the map, you’d see tiny splashes of languages I only know a few phrases in.

But my brain was not born that way; it added color with time.

In Language City, the New York-based linguist Ross Perlin shares his linguistic history—a personal journey most of us never explore. Mine starts like this:

I was born into a Spanish-speaking family, in a city where Spanish is the dominant language, in a country that is erroneously believed to be exclusively Spanish-speaking. However, in Argentina, 25 languages are spoken, 14 of which are Indigenous languages.

I became aware that other languages existed at the age of four. Someone told me that gracias in English was “thank you” (pronounced /senkiu/), and I didn’t quite understand how it worked. What did it mean to speak another language? The explanation I came up with was that, in the United States, when people spoke, they said “thank you,” but through some mechanism I couldn’t yet explain, their ears heard gracias just like I did.

I don’t remember when I realized, or was told, that my theory was incorrect, but it was certainly before I turned six. In first grade, a classmate who took extracurricular English lessons taught me the word “cake.” It was my second word in English, and by then, I already understood that people in different parts of the world used different languages to communicate.

At nine, I started extracurricular lessons like my classmate because English would open doors in the future. I didn’t fully understand what doors and the future felt far away, but I loved the classes. English started making sense, but it was a language confined to the textbooks and the listening activities in a perfect British accent. When I was a teenager, it escaped the classroom and started living on the radio, MTV, and the lyrics of the songs I read in CD booklets.

I went to university, studied translation and teaching, and English became part of my daily life.

In my third year of university, I fell in love with a language for the first time: Portuguese. I continued studying it after completing the two mandatory levels, and today I’ve done nearly a thousand days on the Duolingo app. I do a short lesson every day—two minutes of daily romance with the language of Brazilians.

When I arrived in the United States, I had colleagues from all over the world, and Yasmine from Egypt taught me how to introduce myself in Arabic: Ana ismi Pía (my name is Pía). It was just another phrase in the language exchange game, but it stayed with me, etched in my memory. At the time, I hadn’t met Biko yet, and I had no idea that Arabic would become so important later in my life.

Today, I can greet and have simple conversations, but it’s a tricky language, and just when I think I’ve got the hang of it, new grammatical rules appear, and it slips away again. No matter how slow my progress is, Arabic is one of the three languages of my family, along with English and Spanish, and I’m sure that one day, I’ll manage to use it fluently.

For my master’s degree, I researched Indigenous languages in Latin America, and from my Mapuche colleagues, I learned a few words in Mapuzungun: mari mari (hello or good day), peñi (brother), lamngen (sister), and Wallmapu (the Mapuche territory in Chile and Argentina).

When we started considering moving to Canada, I got closer to French because it’s one of the country’s two official languages. I studied with a teacher for a few months, and sometimes, in addition to Portuguese, I practice French on Duolingo. As a Spanish speaker, French can seem transparent when written, but its spoken form is like diving into a world ruled by anarchy, with too many silent letters and not-so-friendly grammatical rules.

It’s true that Spanish is the language that takes up the most space in my mind. It’s the language I dream in, the one I speak with my grandmother over the phone, and the one I use to curse when I stub my toe against a table leg. It’s the language in which I learned to read and write, and that I share with 600 million people in the world. But it’s not the only language I live in.

A few years ago, I joined a swimming group at the U.S. university where I was doing my scholarship. My dad taught me how to swim before I knew how to write my name, and as a child, I used to train and compete. I loved to swim in open waters (rivers, lakes, the sea), so I can confidently say I’m an expert swimmer. However, on my first day with the swimming group, I had to ask the coach to explain the workout again because I’d never swum in English before.

It’s the opposite in my professional life. I don’t recall ever sending a work email in Spanish. If I had to write one today, I’d doubt my words, tone, and style. My colleagues don’t know my voice in Spanish. Neither do my American friends. They’ve never heard my Argentine accent that sounds more like Italian than Spanish, or how I aspirate the ‘s’ at the end of syllables. With them, I go out for dinner, drink coffee, and gossip in English.

With Biko, we cook in Arabic. If I suddenly wake up in the Middle East tomorrow, I won't be able to say much, but I definitely won't go hungry.

Not long ago, I wouldn’t have described myself as multilingual because we tend to think that multilingualism only belongs to geniuses or scholars who speak many languages perfectly. However, many of us are multilingual to varying degrees of proficiency in different languages, especially migrants.

Did you know that in New York City, where almost 40% of the population is immigrant, more than 700 languages are spoken? According to Ross Perlin, it’s the most linguistically diverse city in the history of the world.

The map of my brain will never look like New York—I doubt I’ll have enough time to learn so many languages—but my mental land does not ask for passports or impose any limits on construction permits. Any language that wishes to live there is welcome.

🎙️A podcast: Fala Gringo

If you love Portuguese like me, or just want to keep in touch with it, you might be interested in this Brazilian Podcast for intermediate learners. The episodes are entertaining and informative, and Leni, the host, does a terrific job discussing current Brazilian affairs and culture.

📚 A book: Language City: The Fight to Preserve Endangered Mother Tongues in New York, by Ross Perlin

“From the co-director of the Endangered Language Alliance, a portrait of contemporary New York City through six speakers of little-known and overlooked languages, diving into the incredible history of the most linguistically diverse place ever to have existed on the planet”.

Have you ever thought about the languages that inhabit your brain, even if they occupy such a tiny corner that you hadn’t realized they were there? What’s your linguistic history? Reply to this email and share!

Reading this on Substack? Drop a comment!

If you came across this newsletter by chance, subscribe to receive my upcoming emails.

If you like what I write and want to help this project grow, you can share A Platypus Life with others.

Until next time!

Maria Pia